At Rooted in Language, we recognize that literacy skills need to be explicitly taught: phonological processing, orthographic knowledge, and morphological awareness (all defined in the previous blog post: What is a Comprehensive LA Program?). We call this skill building. We also know that skills must be efficiently coordinated to achieve fluent reading and writing. We call this consolidation practice. When we put all these components together, consistently practiced through various levels of reading and writing, we call this a multi-linguistic approach.

To understand how we build phonological processing skills, we first need to clarify some terms:

Sound acuity is our ability to hear sounds (i.e. ear and brain receiving sound waves). Is hearing within average range? Do we have hearing loss or chronic ear infections that impede our ability to perceive sounds?

Sound processing is our ability to manage and utilize the sounds we hear. Can we attach meaning to sound? Can we prioritize meaningful sounds and ignore background noise? Can we localize where sounds come from?

Phonemes are meaningful sound units in our language system. Phonemes are the sounds we articulate to make words, and the sounds we hear within words. Different spoken languages across the world have their own set of sounds or phonemes.

Phonological processing refers to a cognitive skill critical to our language development. It is the brain's ability to manage and manipulate phonemes, and to attach meaning to sounds in both spoken and written language. Processing sounds allows a baby to learn that babbling /ma-ma/ attaches to mama/momma, becoming the word mommy; likewise, babbling /da-da/ attaches to dada, becoming the word daddy. Processing is both perceiving and attaching meaning. It is needed for listening, speaking, reading, and writing — the four modes of language that make up the majority of our communication.

(Gesturing, sign, facial expression, intonation, etc., are also forms of communication and must also be perceived and interpreted.)

The American Speech-Language-Hearing Association (ASHA) defines phonological processing as "the use of the sounds of one's language (i.e., phonemes) to process spoken and written language. The broad category of phonological processing includes phonological awareness, phonological working memory, and phonological retrieval."

Phonemic awareness is the ability to track and manipulate sounds (phonemes) in spoken words. It is needed for the foundational literacy skill of attaching meaningful sounds to letters, expanding this entire process into the reading and writing domains. It is a subcategory of phonological awareness, combining all components as essential aspects of phonological processing.

Phonological processing includes the ability to:

• Track sounds and syllables within words, such as saying and hearing two syllables in the word "magnet," as well as recognizing the sounds within each syllable, such as /m-a-g/ and /n-ə-t/. (The vowel sound in the second syllable is a schwa in my midwestern US dialect.) Tracking sounds involves both blending sounds together to read a word and segmenting sounds apart in order to write a word.

• Track sound and syllable changes between words, such as hearing which sound changes between the words "spend" and "spent," or which syllable/sound changes between inflict and inflect.

• Manipulate sounds to change words, such as perceiving and then changing the letter needed to convert the word "then" into the word "than."

Phonological processing is foundational for reading and writing and is an area of weakness for many students with dyslexia and/or dysgraphia. This skill helps learners develop sound-to-letter automaticity, needed to develop word form memories, needed to develop fluent reading and writing skills. Strong processing helps us accurately and efficiently "map" sounds onto letters within a word, often referred to as sound mapping.

Sound mapping requires the phonological system with orthographic knowledge (spelling rules and patterns), attaching sound to spelling within a word, such as:

th ough t (3 sounds) in "thought"

Word form memory, researchers believe, develops when we efficiently bind the sounds we hear (processing) to the spelling we see (orthography). The result is incredibly efficient word storage and word retrieval (sometimes called Mental Orthographic Representations). Fast word recognition helps us quickly attach meaning and grammatical information, needed for comprehension and fluent reading. We also fluently translate meaning into words when we efficiently spell them.

Special Note: Because word form memory includes efficiently tracking sounds attached to spelling patterns, it is not the same as "memorizing" a whole word, as is typically the goal with the disproven notion of "sight words." Sight word practice without sound-to-letter mapping does not aid word form memory and actually hinders efficient reading skills.

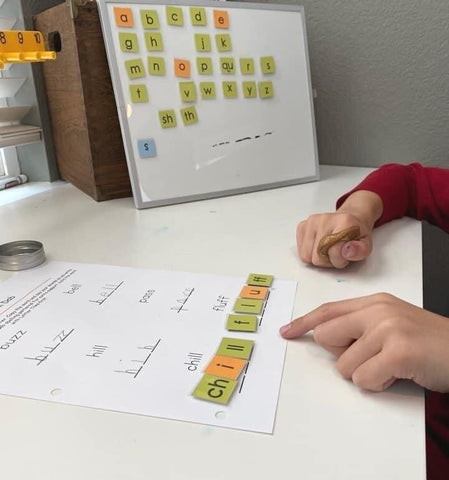

At Rooted in Language, we incorporate phonological processing into our literacy materials because our method of explicit teaching includes blending, segmenting, and manipulating sounds. We draw upon the oral language system, connecting meaning to sounds — whether or not letters are present. But also, we always connect sounds to letters, using Letter Tiles, sound lines, "saying sounds" while writing, or marking text while reading with a pencil.

Students with strong processing skills will find phonological practice to be easy and enjoyable. Their word mapping will be efficient and their word form memory will be evident. Their morphology skills will be more intuitive.

Students with weak processing skills will have difficulty with phonological practice. They may tire easily or even resist, but they need this practice the most to improve their word mapping and word form memory. To help students tolerate this difficult but necessary learning, lessons should be short and frequent — with many brief practice sessions a week, continuing throughout the year.

Don't give up on phonological processing practice! Research and experience have shown that phonological processing practice along with phonemic awareness strategies promote reading and writing progress. This ability is foundational for literacy development.

Rooted in Language provides research-based multimodal products, classes, and instructional methods for teaching learners of all ages and skill levels, especially those who struggle with dyslexia, dysgraphia, developmental language disorder, and other language difficulties. We focus on giving you, the educator, the tools you need for deep, explicit literacy instruction. For help on where to start, view our Placement Guide or our Pinwheels Comprehensive Early Literacy Curriculum.